Virus-membrane interactions

A well established usage case for cryo-TEM is three-dimensional reconstruction of isolated macromolecules, virus particles, or filaments. On one hand, these approaches are based on averaging of repetitive structures – either due to numerous identical molecules, repetitive patterns on a filament, or symmetries, to reduce the noise inherent to cryo-TEM. On the other hand, different views of these complexes required for three-dimensional reconstruction can be either obtained from (ideally) random orientation of the particles in the ice or from the helicality of filaments.

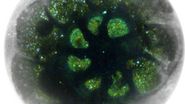

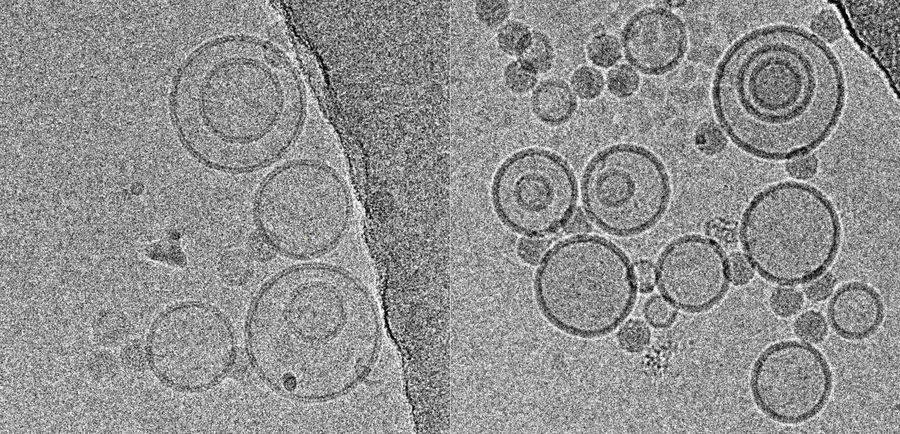

Mohit Kumar from Dieter Blaas' Group at the Max F. Perutz Laboratories (Vienna) was interested in the interaction of rhinovirus particles with lipid membranes and the events leading to endocytosis of the particles [1]. They decided to employ single particle reconstruction methods to obtain three-dimensional models of the particles docking to artificial membranes (liposomes), using numerous individual virion/membrane complexes selected from many micrographs.

For collection of many micrographs, as required by this type of experiment, or for freezing of numerous grids of similar specimens, reproducibility of results – in this case ice thickness and minimized contamination – is a major factor. The Leica EM GP addresses problems with blotting intensity arising from moist, flexing filter paper or bent grids with a unique sensor: this sensor detects the moment of contact between the filter paper and the sample droplet, establishing a reference point. By moving the filter paper forward by a defined distance from this reference point, the pressure applied varies very little from one grid to the next, yielding highly reproducible results if the same specimen, volume and timing are being used.

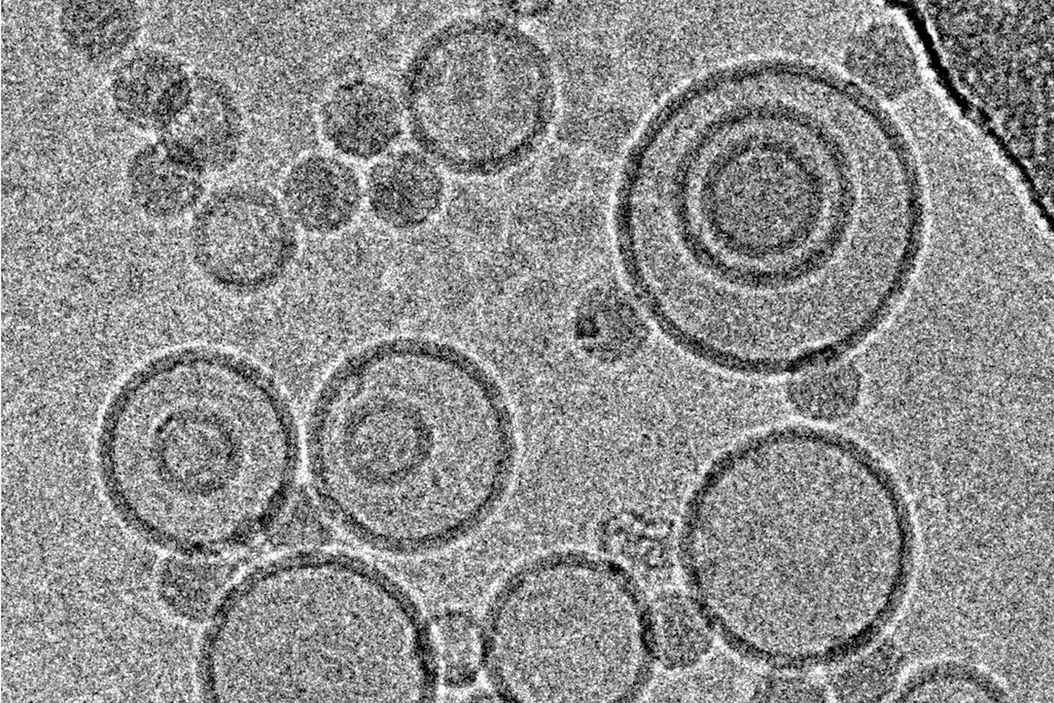

Using this blotting sensor, results could be obtained very efficiently from 4 µl samples applied onto glow discharged 400 mesh Cu grids with a R1.2/1.3 Quantifoil film that were allowed to spread for 25 seconds in the environmental chamber with 99 % humidity and 30 °C. Subsequently, they were blotted for 0.8 seconds and plunged into liquid ethane. Particles binding to liposomes of similar diameter were picked from the micrographs of these frozen and unstained specimens acquired on a 300 kV cryo-TEM (Figure 1). From these selected particles, the authors calculated reconstructions of the virus/membrane assemblies in absence of cellular receptors, mimicking the intimate contact of lipid membranes over a twofold axis of icosahedral symmetry, illustrating the binding mechanism of the tight virus-membrane complex (Figure 2).

Baculovirus actin comet tails

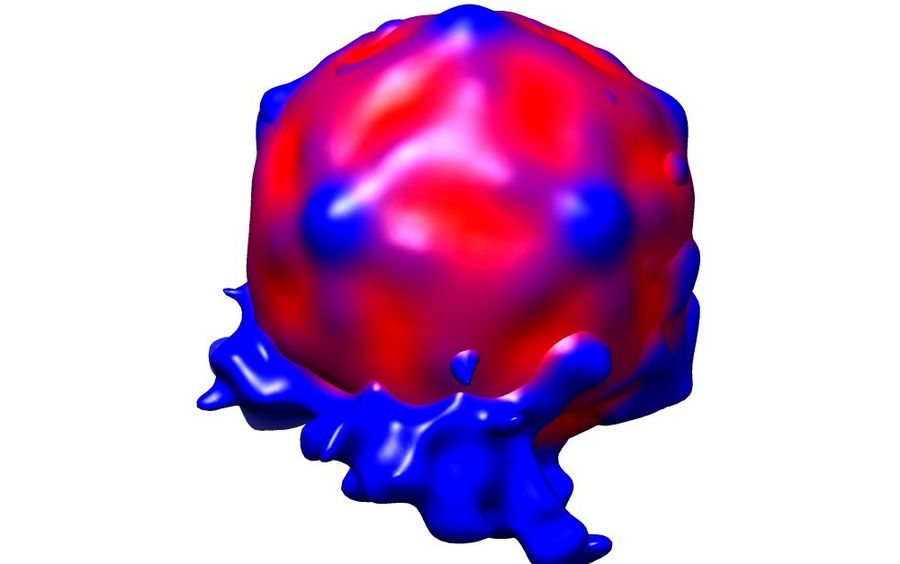

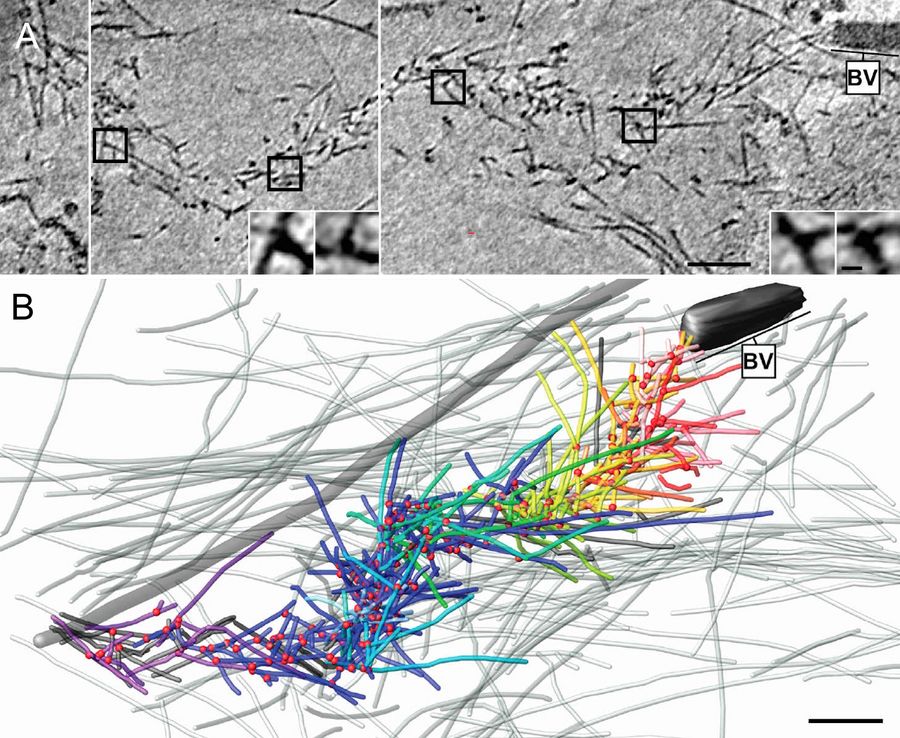

Jan Mueller and colleagues from J. Victor Small's lab at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, Vienna [2] used cryo-electron tomography to investigate the actin cytoskeleton in baculovirus "comet tails", both in vivo as well as in vitro. These actin tails are nucleated by baculovirus and other pathogens to drive their own propulsion, essential to disseminate the infection. They serve as a popular and well accessible model systems to study the architecture of the actin cytoskeleton and the role of regulatory proteins.

For the in vitro experiments with actin tails polymerized from synthetic (and easy to manipulate) "motility cocktails", the tails were not pipetted onto the grids just before freezing, to prevent damage by manipulation. Instead, they were "grown" directly on Quantifoil R3.5/1 perforated carbon films on 200 mesh Au grids. After supplementing the sample with 10 nm protein coated colloidal gold serving as fiducial markers for alignment in electron tomography, it was transferred to the humidified chamber of the EM GP. Samples were blotted 1.2 to 1.6 s from the back side, subsequently frozen by plunging into liquid ethane just above freezing temperature, and stored under liquid nitrogen until loaded into the microscope. To reduce background, zero-loss filtered tilt series were acquired with SerialEM over the holes of the perforated carbon film at 300 kV and reconstructed offline with IMOD (Figure 3).

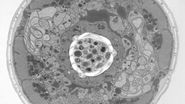

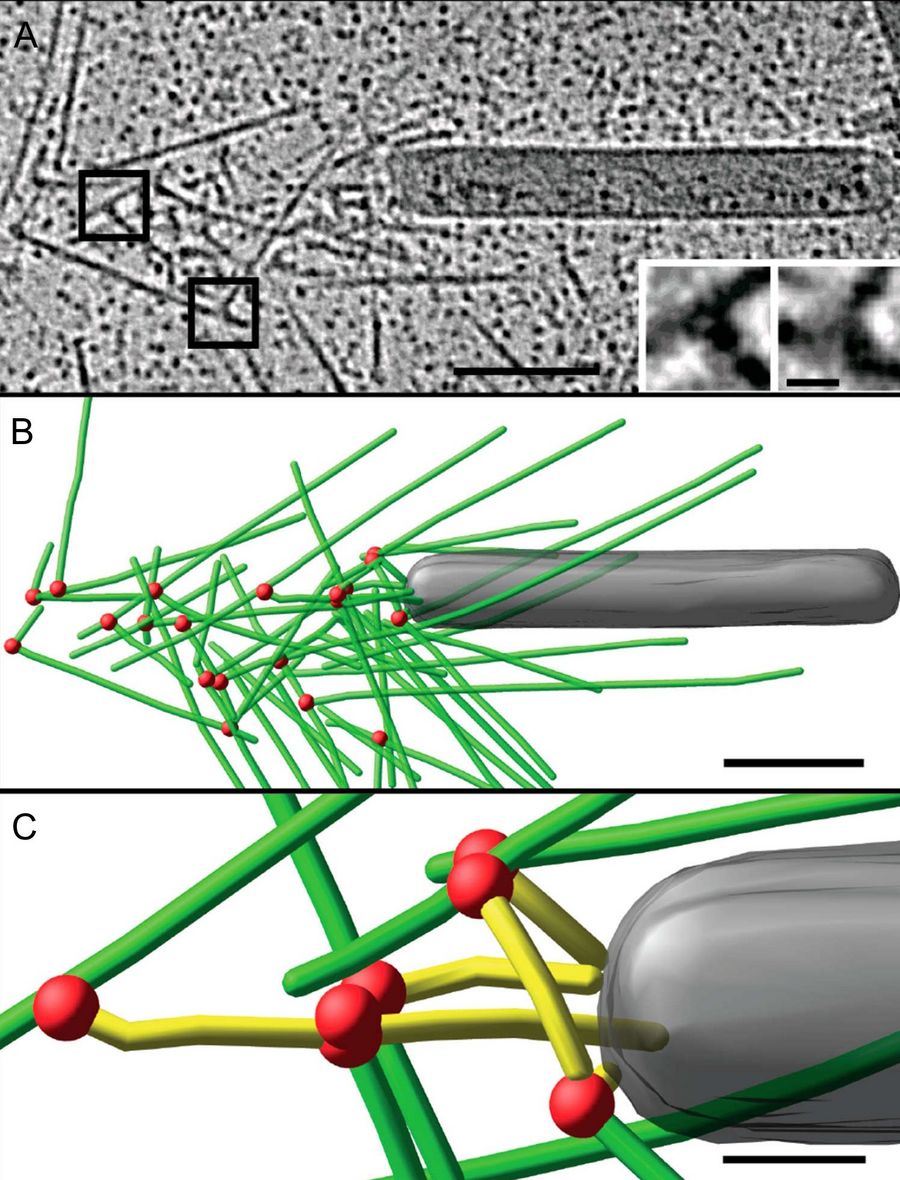

For another part of the study, baculovirus actin comet tails were visualized by Mueller and colleagues inside the thinly spread part of living cells that is is accessible to examination by cryo-electron microscopy. The investigation of this region was greatly advanced by the introduction of cryo-electron tomography and the ability to resolve superimposing structures in three dimensions [3].

For these in vivo experiments, cells were cultured on 200 mesh gold grids, to eliminate cytotoxic effects by copper ions and obstruction by grid bars at high tilts in electron tomography. A perforated carbon support film such as Quantifoil R1/4 was used. Once the cells had attached and spread, they were chemically fixed and extracted to clear the cytosolic background, enabling reliable tracking of individual filaments. Subsequently, samples were covered with 4 µl of medium supplemented with 10 nm protein saturated gold particles and transferred to the environmental chamber of the EM GP at 95 % relative humidity. These samples benefited greatly from the design of the blotting mechanism on the Leica EM GP: due to unilateral blotting, excess liquid was only blotted away from the back side of the grid, direct contact between the sensitive cell monolayer and the filter paper is avoided. Blotting times of 1.5 to 2.0 s with pre-humidified Whatman No. 1 filter paper yielded best results, using the holes in the C film to obtain an even ice thickness all over the grid. After blotting, the samples were plunged immediately into liquid ethane. Tomography data were acquired and processed as described above (Figure 4).

Pharmaceutical nanocarriers

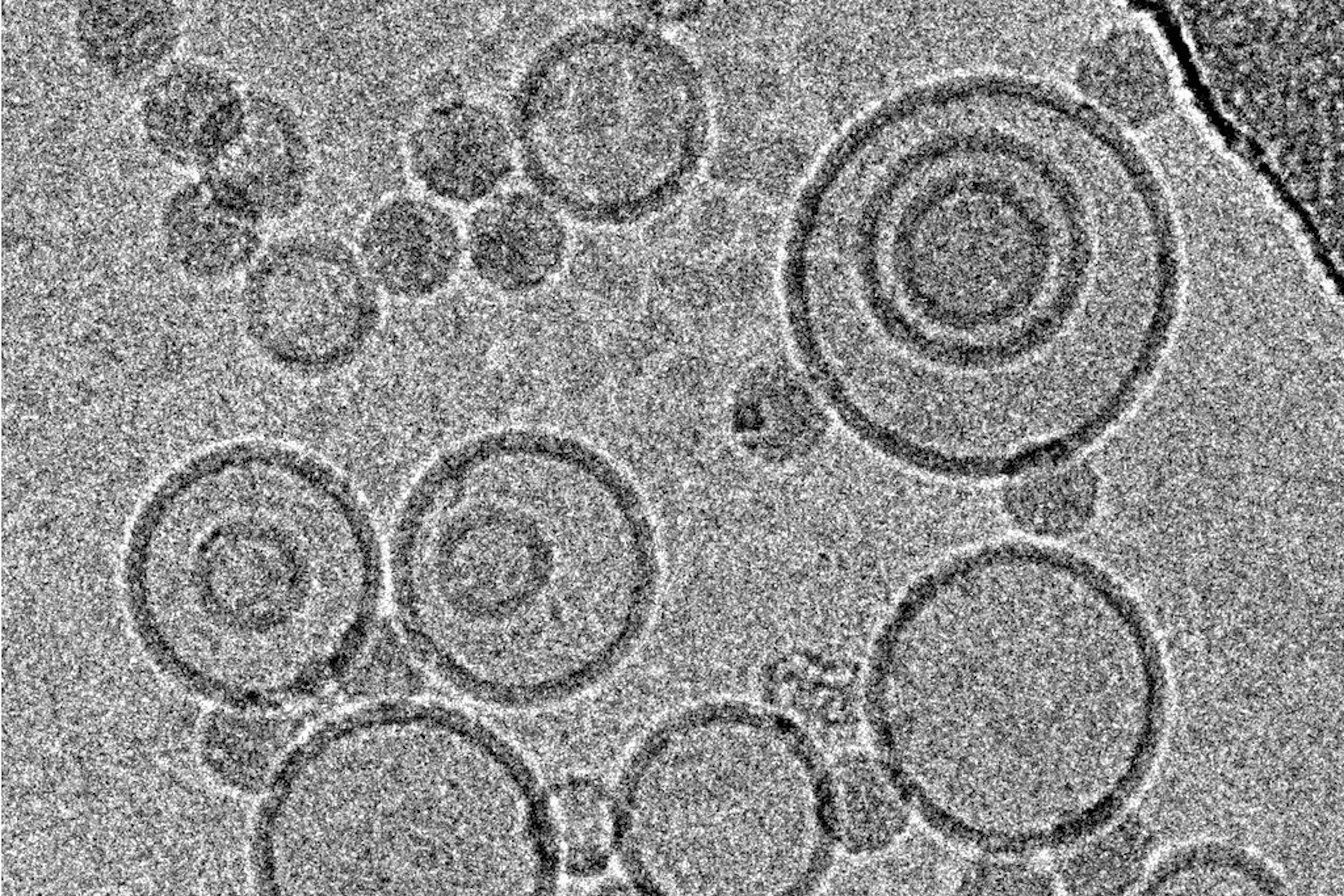

Immersion freezing and cryo-TEM are not only indispensable tools in structural and cellular biology, but also very useful for imaging of pharmacological specimens in their natural state (for a review, see [4]). A study by [5] used cryo-TEM of immersion frozen specimens to elucidate the ultrastructure of different ultrasound-engineered nanocarriers for dermal drug delivery: solid lipid nanoparticles, nano-structured lipid carriers, and nanoemulsions were visualised.

Samples for these experiments were frozen on a Leica EM GP, the instrument’s environmental chamber was operated at room temperature and 95 % rH. The optimal dilution of each specimen in double distilled water was obtained from a series of pre-tests, to yield a good density of specimen with not too much overlap between individual structures. 4 µl of the specimen were applied onto a glow discharged 400 mesh EM grid coated with perforated carbon films. After a settling time, the suspension was blotted for 1.25–4.0 s, depending on the formulation used. Standard Whatman No. 1 filter paper and the instrument’s blotting sensor were used, the sample was immediately plunged into liquid ethane after blotting.

While size information from cryo-TEM was complementary to data obtained form dynamic light scattering, structural information was exclusive to cryo-TEM and showed quite dramatic differences between individual specimens, ranging from spherical droplets to flat, flake-like structures (Figure 5). Please note the absence of contamination in the micrographs presented here, owing to quick handling and a number of anti-contamination measures integrated in the GP: this includes negative pressure in the environmental and a powerful "TF" evaporator in the primary cryogen, that creates an atmosphere of dry and cold N2 gas, to protect the specimens from warming up and contamination.

Fundamentals of immersion freezing Cryo-transmission electron microscopy

The high vacuum required in a transmission electron microscope (TEM) greatly impairs the ability to study specimens naturally occurring in an aqueous phase: exposing "wet" specimens to a pressure significantly lower than the vapour pressure of water will lead to the water phase boiling off rapidly in the column, with devastating consequences for the structure of the specimen. Hence, various methods to dry specimens before inspection are employed in conventional TEM – a preparative step often associated with artifacts limiting the significance of the results.

Cryo-transmission electron microscopy

An approach addressing both the problem of drying during specimen preparation and the issue of volatility of water in the microscope's vacuum is inspection of the samples in a special holder at –180 °C and below, in a frozen state with only minimal sublimation rate. This technique, known as cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) or transmission cryo-electron microscopy has become an indispensable tool in structural biology over the last decades and, with the advent of cryo-electron tomography, also in cell biology.

For samples that are inherently thin enough such as isolated macromolecular complexes, viruses, or small cells, specimen preparation for cryo-TEM can be essentially reduced to one step: physical fixation by immersion freezing (plunge freezing).

Immersion freezing

One prerequisite for successful visualization of a sample embedded in ice is arresting the water molecules in place within a time so short not allowing the formation of ice crystals, ideally resulting in amorphously frozen (vitrified) water. In case of immersion freezing, this can be achieved only if a suitable cryogen with high thermal conductivity is being used and if the sample is immersed quickly to ensure quick freezing all over. Suitable cryogens include liquified ethane, propane, or a mixture of both [6] used just above the melting point (–183 resp. –188 °C for the pure compounds). Furthermore, the distance of any point in the specimen to the surface exposed to the cryogen has to short, i.e., the sample must be very thin.

Specimen carriers in cryo-TEM have to provide good support for the specimen, yet very little background not to reduce the low contrast of typically unstained cryo-samples any further. They also have to be conductive to avoid charging of the specimen and related problems such as drift. All these requirements are satisfied to some extent by standard TEM grids with a perforated carbon film, either of the lab-made type or the commercially available ones. The latter feature holes of very regular size and position easing automated data acquisition. Pre-treating the grids with glow discharging/plasma cleaning or coating with matrix proteins can be required to allow even spreading of aqueous solutions or attachment of cells.

For basic immersion freezing, a grid held by a forceps is fixed in a guillotine-like apparatus (Figure 1), a small quantity (3–5 µl) of the specimen in aqueous solution is applied, and the major part of the solution is blotted off with filter paper to reduce the thickness of the residual layer. This step is necessary both to allow vitrification (see above) and also to achieve a thickness that can be penetrated by the electron beam of the microscope, as for most samples, no further preparative steps are to be employed. The exact thickness depends on the sample and on the microscope available, typically ice layers as thin as the sample allows, but no thicker than 500 nm are being aimed for. This is also well within the range of thicknesses that can be frozen reliably by the technique described.

Immediately after blotting, the sample is plunged quickly into the cryogen. After freezing, the specimen can be transferred to LN2 to be stored almost indefinitely before inspection in the microscope.

Challenges

A key issue is producing vitreous ice by sufficiently fast cooling, but also maintaining the ice in this amorphous state: the latter requires that the sample is kept constantly below recrystallisation temperature. This can be ensured by keeping the grid below LN2 or in a cold N2 gas atmosphere and pre-cooling all tools required for manipulation of the frozen specimen.

Another major issue is contamination of the frozen specimen by humidity condensing on its surface, forming nanometer size ice crystals. As the sample will be imaged frozen and as a whole (in contrast to methods like freeze substitution or Tokuyasu cryosectioning, where superficial crystals are removed by subsequent processing steps), this contamination will be evident as high contrast features in the TEM, that have to be avoided. This can be achieved by a number of provisions, aiming to reduce the humidity of the surrounding atmosphere and the time the sample is exposed to this atmosphere: typically, a dehumidified room is preferable, the sample should be kept below LN2, breathing onto the sample has to be avoided, all transfers should be performed quickly in the dry (and cold) N2 atmosphere just above the liquid phase using clean tools, and the microscope has to supply a clean vacuum in the objective area via a special anti-contamination device.

Even a perfectly frozen sample, however, will fail to produce results of significance if it was not treated well in the moments before freezing. One potential source of problems is the uncontrolled temperature of the specimen on an instrument. Located in an undefined position above a vessel containing LN2, the sample be exposed to room temperature or cold gases, leading to an ill characterized state.

On the same type of instrument, especially if working in a room with lowered humidity as recommended above, problems can arise from evaporation of the solvent: according to [7], water evaporates at a rate of 50 nm/s from a thin film at room temperature and a surrounding humidity of 30 %. This removal of solvent and the consequent enrichment of salts and other solutes can obviously critically influence the results obtained from aqueous specimens.

Even though basic instruments as the ones in Figure 1 have yielded very meaningful results in the hand of experienced researchers, many of the issues addressed above remained unsolved. Hence, labs have started building their own instruments with environmental chambers and automated blotting mechanisms. Commercial products by different manufacturers followed soon (for a review see [8]), including the Leica EM GP immersion freezer from Leica Microsystems, developed in collaboration with the IMP/IMBA Electron Microscopy Facility, Vienna.

Recommended reading

- Resch GP, Brandstetter M, Königsmaier L, Urban E, and Pickl-Herk AM: Immersion freezing of suspended particles and cells for cryo-electron microscopy. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 803–14 (2011).

- Resch GP, Brandstetter M, Wonesch VI, and Urban E: Immersion freezing of cell monolayers for cryo-electron tomography. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 815–23 (2011).

![Cryo electron microscopic images of nano-structural lipid carriers (NLC), nanoemulsions (NE) and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) Cryo electron microscopic images of nano-structural lipid carriers (NLC), nanoemulsions (NE) and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) (Schwarz JC et al.: Nanocarriers for dermal drug delivery: Influence of preparation method, carrier type and rheological properties. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 437: 83–88 [2012], Fig. 2).](/fileadmin/_processed_/c/9/csm_Nano-structural_lipid_carriers_08abfc2f56.jpg)