Challenges concerning live-cell imaging

Live-cell imaging involves capturing images of living cells, organoids, tissues, or whole organisms. The images can be static or time-lapse sequences. Its use has grown with advances in optics, electronics, and fluorescent tagging, making it more accessible and powerful. Two key advantages of live-cell imaging make it essential for modern biological research:

- observing cells without fixation-induced artifacts and

- monitoring dynamic cellular processes in real time.

Capturing fast physiological events, like calcium signaling or mitochondrial changes, requires high frame rates, sometimes even milliseconds per frame. To ensure meaningful results, maintaining cell health is critical.

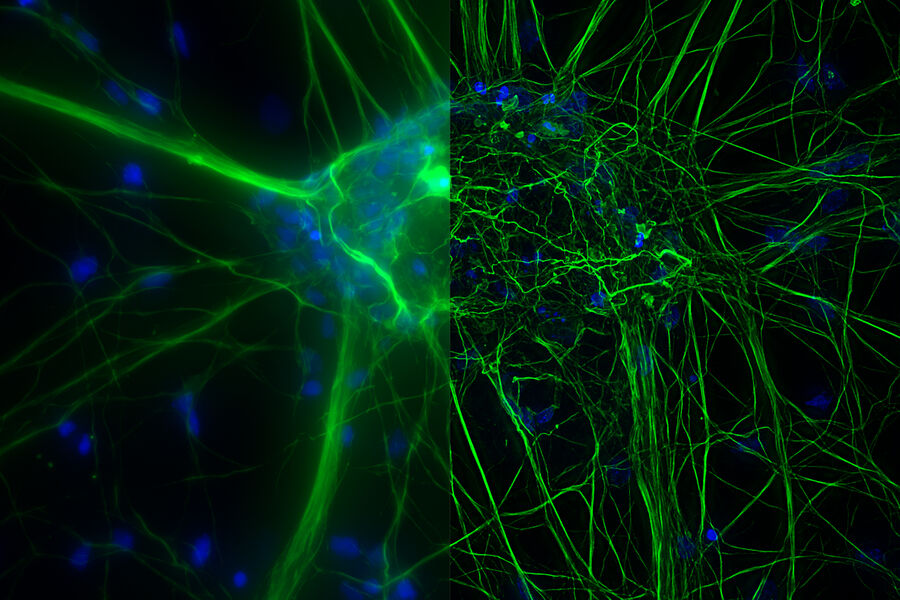

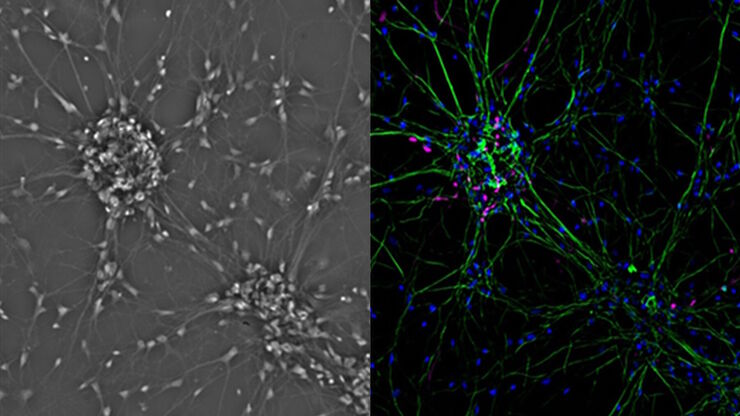

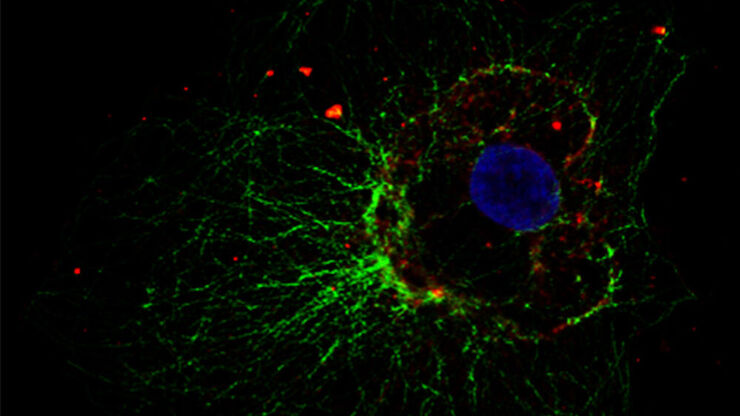

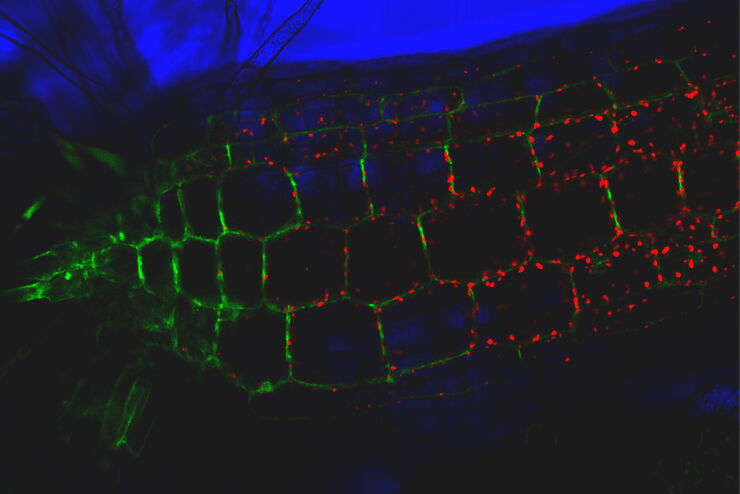

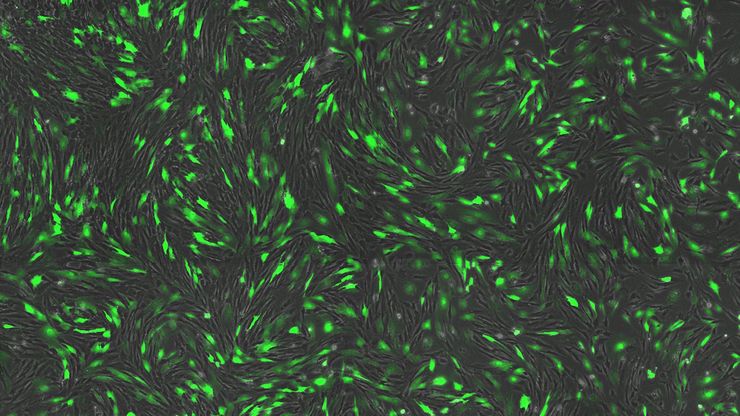

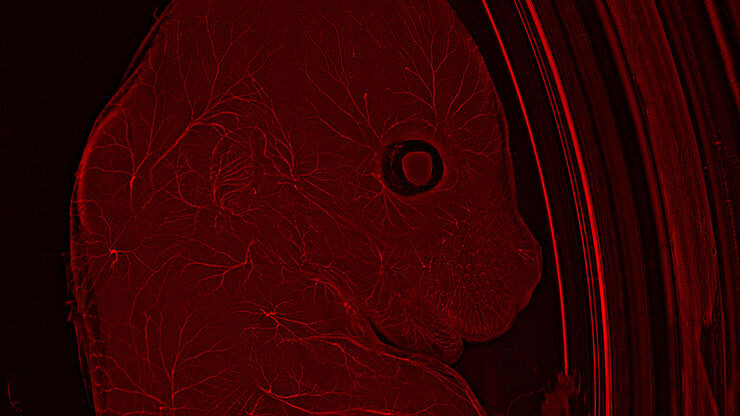

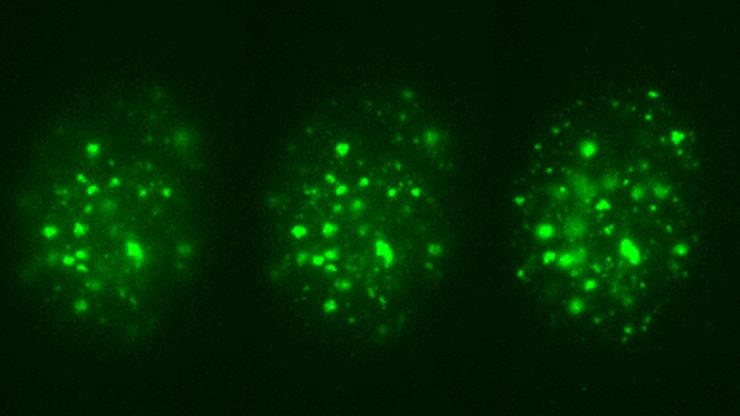

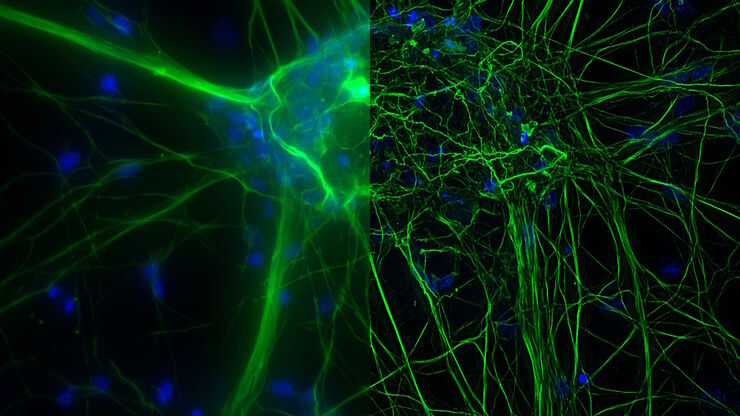

Cultured cortical neurons where green indicates beta-III-tubulin and blue nuclei. The slider shows a raw widefield image compared to one with Large Volume Computational Clearing (LVCC). An image stack of 59 planes was acquired using a THUNDER Imager 3D Cell Culture microscope. Sample courtesy of FAN GmbH, Magdeburg, Germany.

Maintaining cell viability during imaging

- Media: Mammalian cell culture requires temperature and pH control, buffering (CO2 or HEPES), and nutrients and serum.

- Culture Vessels: Image quality depends on the vessel where glass-bottom and coated options are preferred.

- Sterile Technique: Maintaining sterility is vital for cell culture, especially concerning antibiotic-free protocols.

- pH regulation: pH is controlled with chemical or CO2-based buffers and specialized incubation chambers.

- Phototoxicity: Cell damage during fluorescence imaging is prevented by minimizing light exposure with sensitive cameras and low-intensity illumination.

- Focus Drift: During long-term imaging it is managed through thermal stability, specialized hardware, and autofocus.

Basic articles on live cell imaging

Introduction to Live-Cell Imaging

Introduction to Mammalian Cell Culture

Live Cell Imaging Gallery

Physiology Image Gallery

Contrast methods and live-cell imaging

Live cells are essentially colorless. Some experimental setups do not allow contrasting dyes and labels. For these cases, microscopy techniques take advantage of phenomena, like reflectance, birefringence, light scattering, and diffraction, to achieve optimal contrast.

- Phase Contrast Microscopy: It translates phase variations into image contrast. Ideal for imaging thin, live, unstained specimens. Prone to halo artifacts with thicker samples.

- Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) Microscopy: DIC uses polarized light and refractive index differences to generate shadowed, high-resolution images of unstained biological samples, but limited to glass vessels.

- Integrated or Hoffman Modulation Contrast (IMC or HMC): It converts phase gradients into brightness differences using a zoned amplitude filter to produce pseudo-3D images. IMC/HMC is compatible with plastic vessels.

Related articles on contrast methods

A Guide to Phase Contrast

Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) Microscopy

Integrated Modulation Contrast (IMC)

Epi-Illumination Fluorescence and Reflection-Contrast Microscopy

Optical Contrast Methods

Fluorescent live-cell imaging

Fluorescence is a form of luminescence. It is used often with microscopy to: determine the distribution and quantification of single molecules in cells, study colocalization and interactions, and examine processes like endocytosis and exocytosis. Fluorophores can be attached to antibodies (immunofluorescence), genetically expressed, or used as biochemical sensors.

Related articles on fluorescence microscopy

How to Prepare your Specimen for Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Applications of TIRF Microscopy in Life Science Research

Ratiometric Imaging

Live-Cell Imaging Techniques

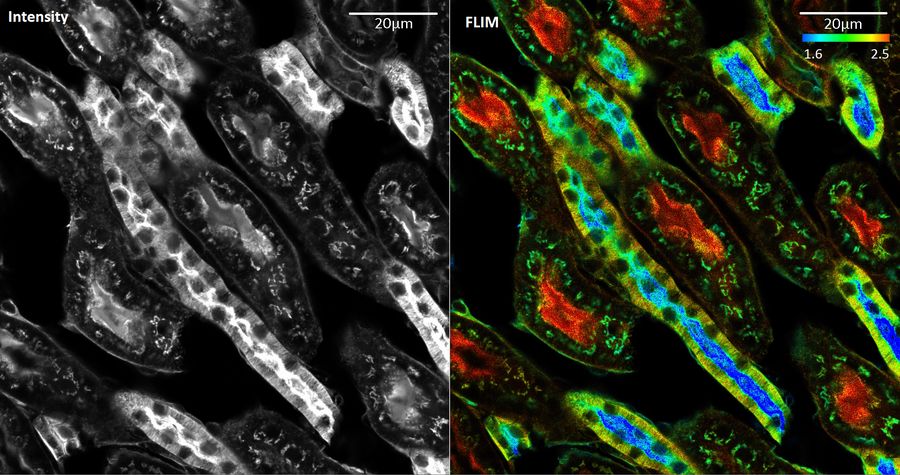

A Guide to Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM)

Photomanipulation and live-cell imaging

Photomanipulation uses light to activate, alter, or disrupt fluorophores or cellular structures and is used to investigate live-specimen processes.

- Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), FLIM-FRET, and Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET): They measure protein interactions within cells.

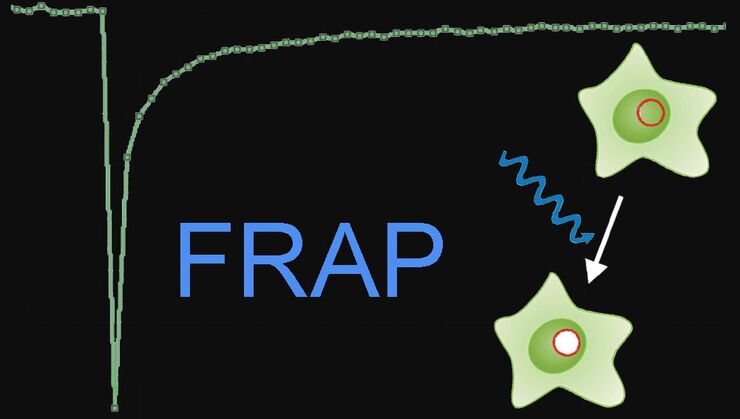

- Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP), inverse FRAP (iFRAP), and Fluorescence Loss in Photobleaching (FLIP): They track protein dynamics using fluorescence recovery, inverse loss, or continuous depletion across cellular compartments.

- Photoactivation, Photoconversion, and Photoswitching: They manipulate fluorophore states to follow protein localization, dynamics, and expression.

- Optogenetics: It uses light-sensitive proteins to monitor cell-signaling pathways.

- Cutting and Ablation: Lasers cut out or destroy specific cellular structures to investigate development, wound healing, and regeneration.

- Uncaging: UV light activates “caged” compounds to release neurotransmitters, ions, or nucleotides.

Related articles on Photomanipulation

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP) and its Offspring

Photoactivatable, Photoconvertible, and Photoswitchable Fluorescent Proteins

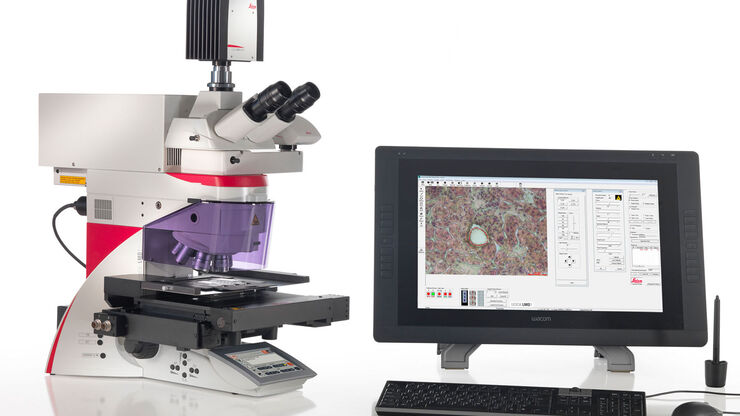

Choosing a live-cell imaging microscope

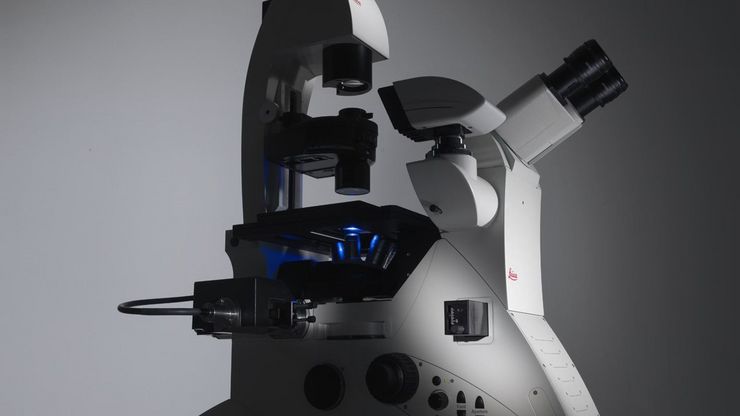

An inverted microscope is routinely used for live-cell imaging. It provides certain advantages over a standard upright microscope:

- Working distance: The space between the specimen and condenser lens for inverted microscopes at sharp focus, as the objective lens is under the stage. Large working distances are achievable.

- Access to the cell media: The space above a vessel on an inverted microscope stage is easily accessible, so specimens can be taken from the medium or substances added to it efficiently.

- Optimal imaging of cells: Usually cells grow adhesively or settle on the bottom of vessels and wells. Thus, it is easier to image them with an inverted microscope. There is little or no risk the objective contaminates the media.

Articles on microscope selection for live-cell imaging

Factors to Consider When Selecting a Research Microscope

How to Determine Cell Confluency with a Digital Microscope

Dual-View LightSheet Microscope for Large Multicellular Systems

How To Perform Fast & Stable Multicolor Live-Cell Imaging - full article

How Artificial Intelligence Enhances Confocal Imaging

Real Time Images of 3D Specimens with Sharp Contrast Free of Haze

Cell culture and biomedical research

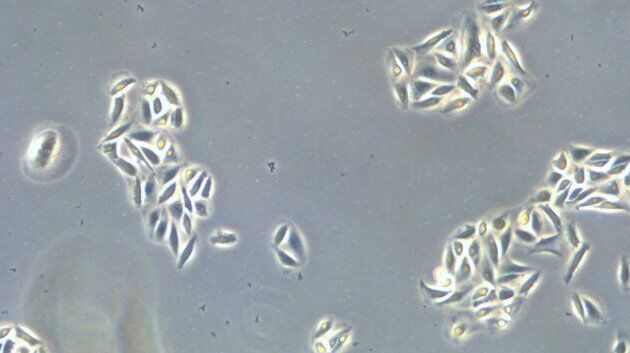

Cell culture is a cornerstone of biomedical research, enabling studies in fields like cell biology, immunology, and cancer research. Cells are classified by morphology (fibroblastic, epithelial-like, lymphoblast-like cells), type (immortalized, primary, or stem cells), and organizational structure (2D monolayers to complex 3D organoids or organ-on-a-chip systems). Culture conditions require 37 °C, sterile environments, nutrient-rich media, and pH control via buffering. Inverted microscopes are essential for imaging of cell cultures, using contrast techniques like phase contrast or fluorescence. Advanced setups support precise monitoring of cell health, confluency, and genetic expression. A flexible system enables realistic disease modeling, drug screening, and personalized medicine thanks to technologies like iPSCs (induced pluripotent stem cells) and 3D cultures.

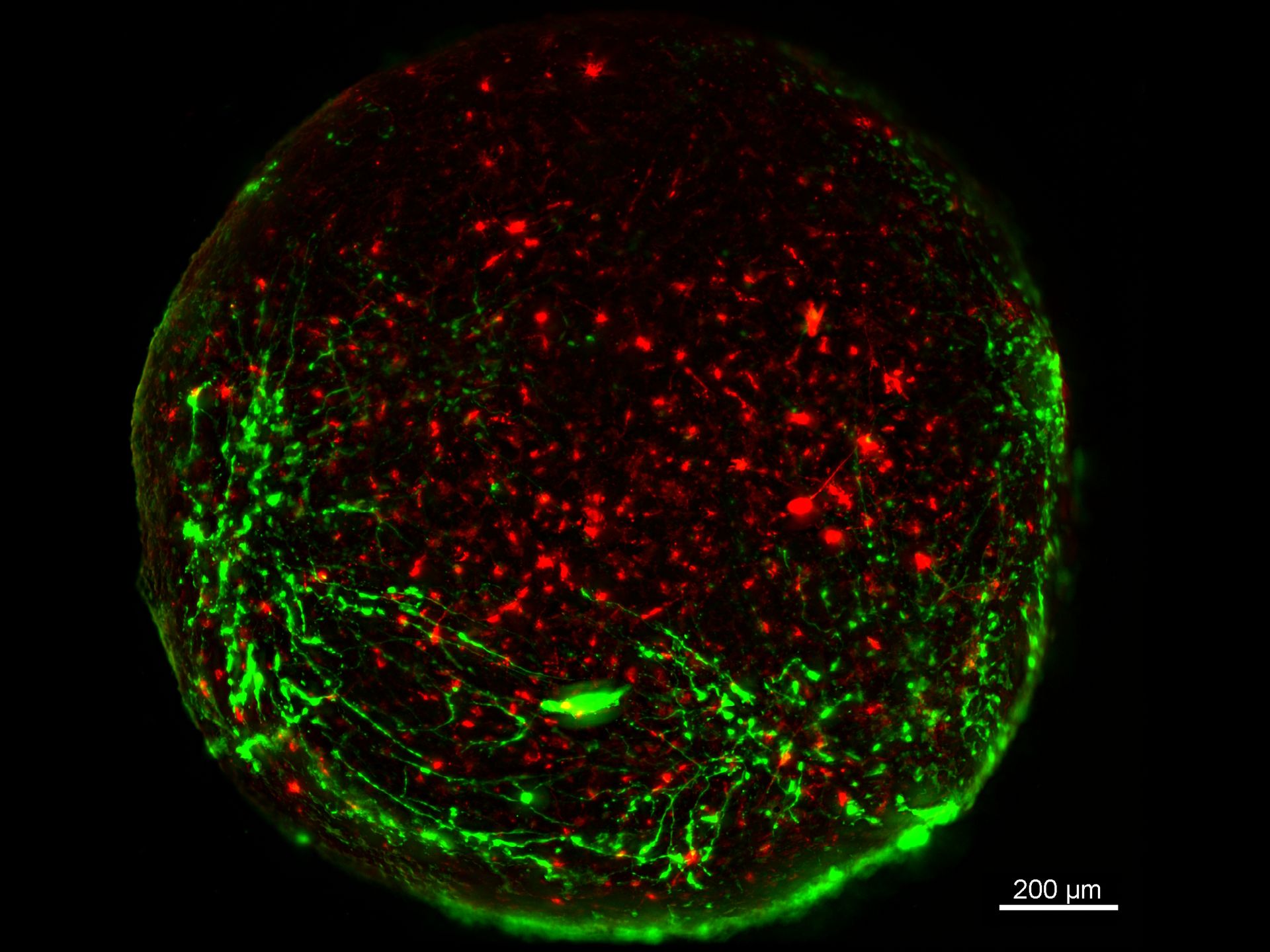

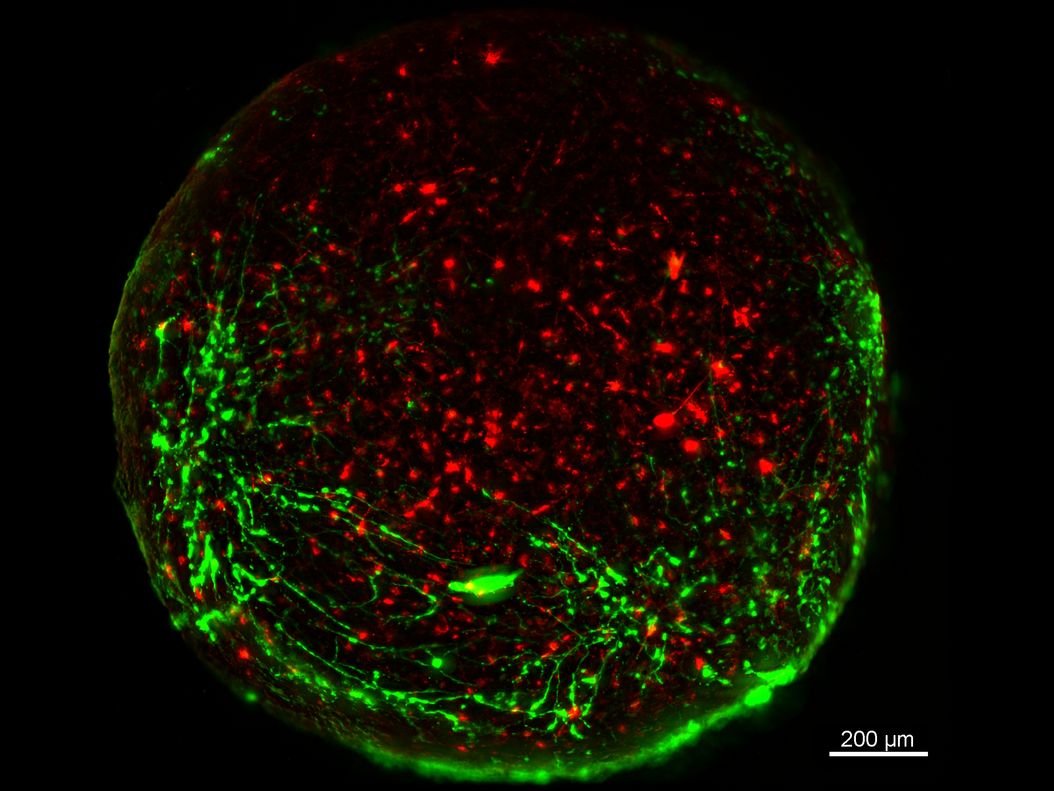

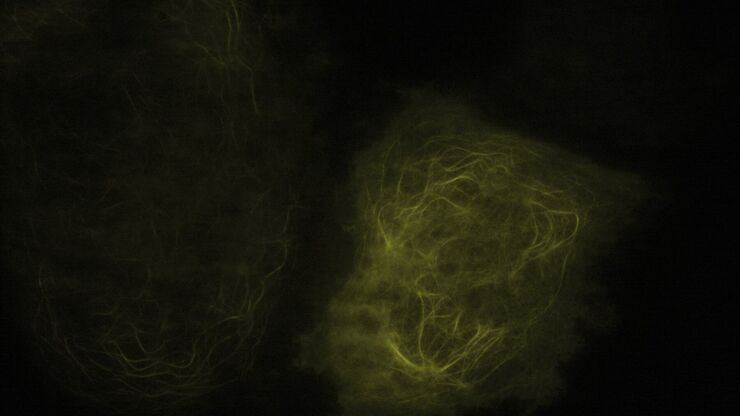

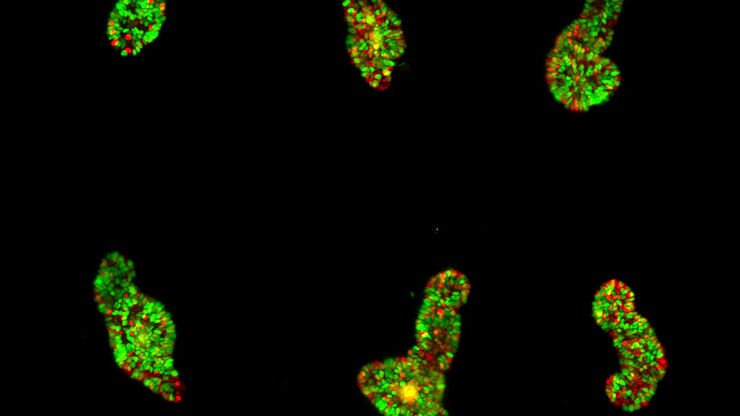

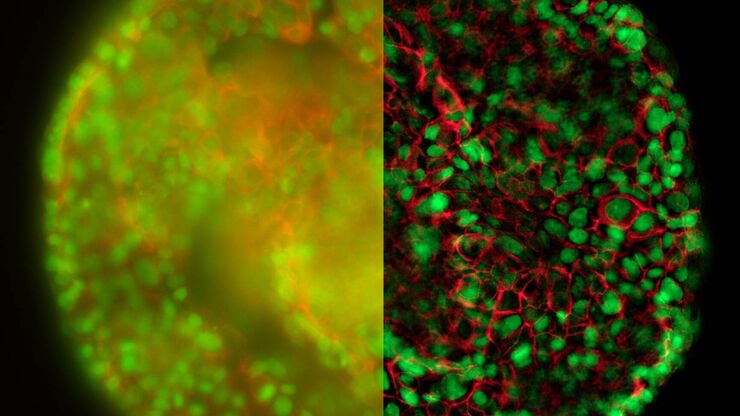

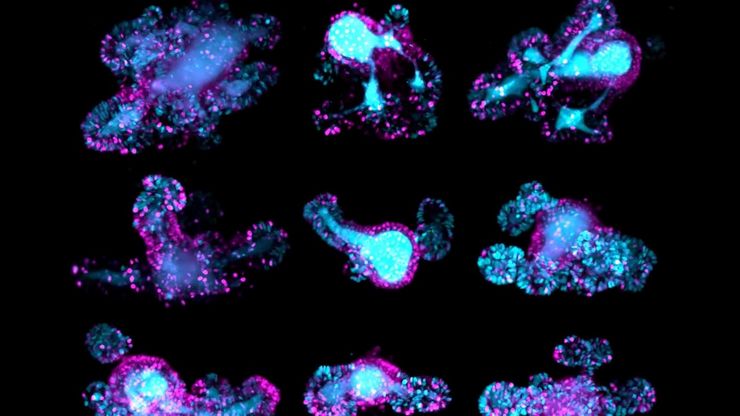

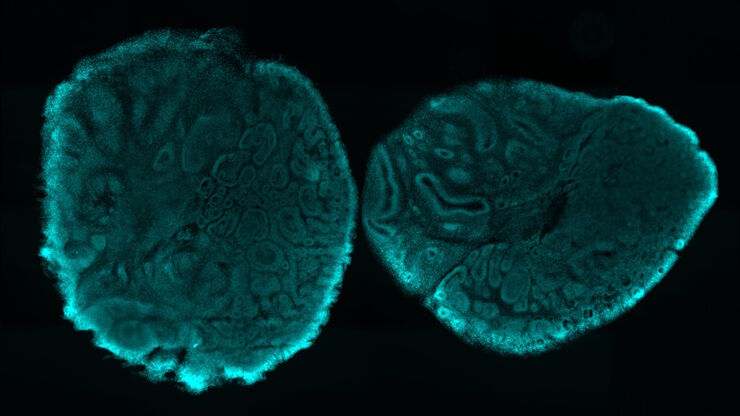

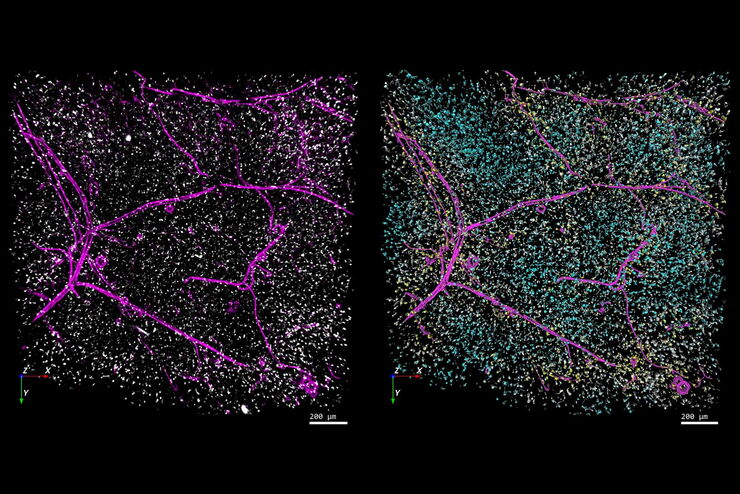

Mouse lung organoids derived from alveola stem and progenitor cells imaged with a THUNDER Imager 3D Cell Culture. Sample courtesy P. Kanrai, MPI for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

Related articles on cell culture

Microscopy and AI Solutions for 2D Cell Culture

Precision and Efficiency with AI-Enhanced Cell Counting

Leveraging AI for Efficient Analysis of Cell Transfection

Designing the Future with Novel and Scalable Stem Cell Culture

Introduction to 21 CFR Part 11 for Electronic Records of Cell Culture

How to do a Proper Cell Culture Quick Check

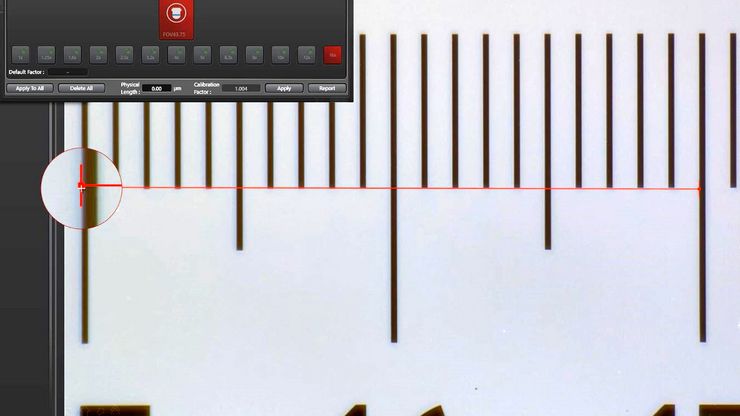

Dissection of living cells

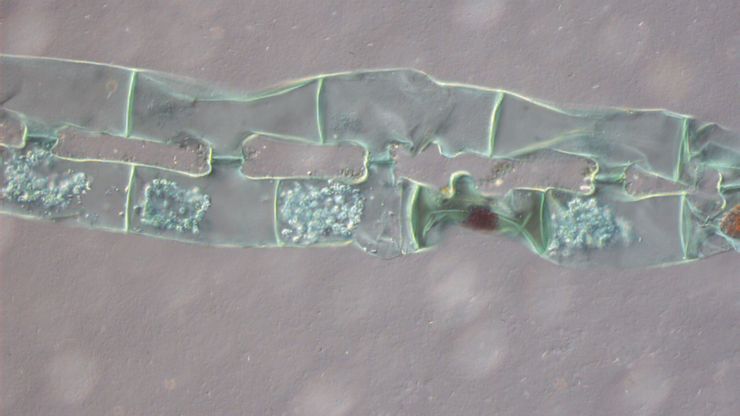

Laser microdissection (LMD) is a precise technique used to isolate single cells or specific regions from tissue sections using a focused laser beam. It enables contamination-free collection of targeted cells without affecting neighboring areas, making it ideal for downstream applications like DNA, RNA, or protein analysis. The process typically involves visual identification under a microscope, followed by laser cutting of the desired cell into a collection device. This method is widely used in cancer research, pathology, and genomics, particularly when analyzing heterogeneous specimens. Even though LMD is primarily used for fixed tissues, it is also applicable to live cell cultures and thin tissues with some restrictions.

Articles on dissection of living cells

Biomarker Discovery with Laser Microdissection

Consumables for Laser Microdissection

An Introduction to Laser Microdissection

Live imaging of model organisms and 3D organoids

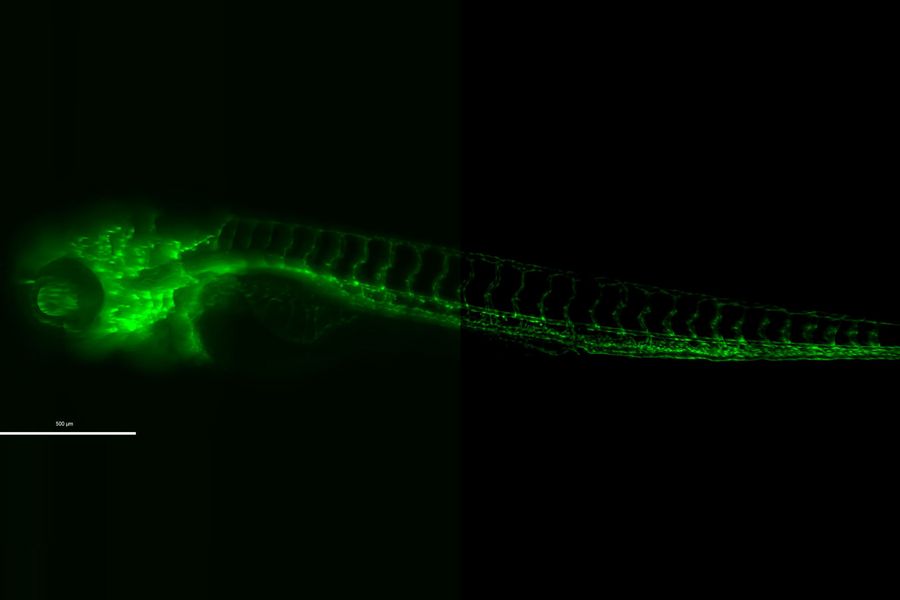

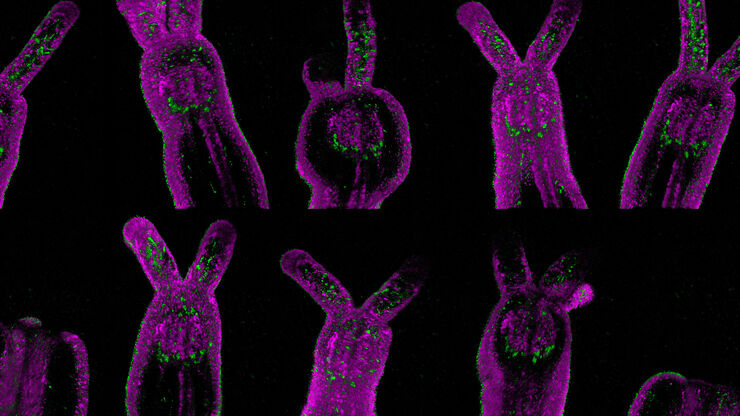

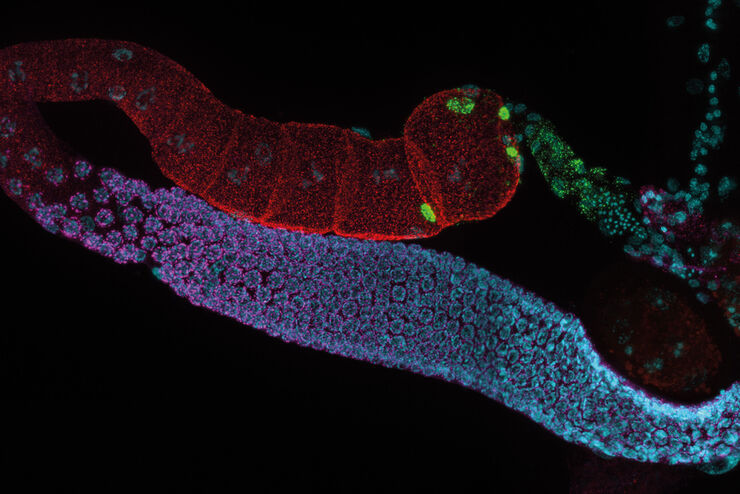

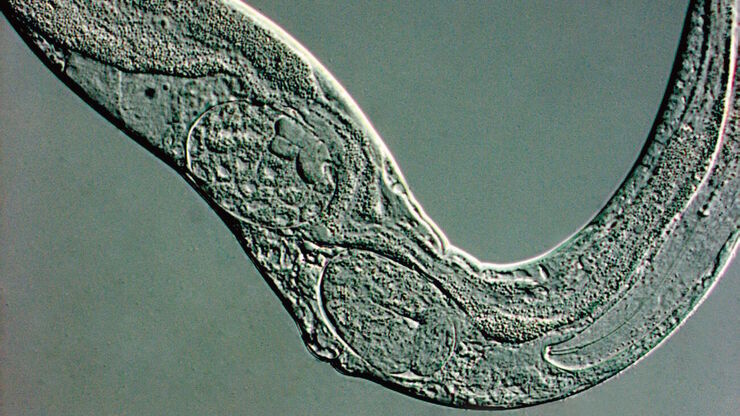

Detailed, physiologically relevant imaging of complex biological systems, like model organisms and 3D organoids, is done with optical microscopy. Model organisms, such as zebrafish, Drosophila, or C. elegans, are genetically tractable biological systems used to study development and disease processes in vivo. Meanwhile, 3D organoids, i.e., miniaturized, stem cell-derived versions of organs, mimic native tissue architecture and function. Advanced microscopy techniques, including confocal, light sheet, and fluorescence microscopy, allow researchers to visualize cellular dynamics, structure, and interactions in real time and 3 dimensions. These tools are essential for uncovering mechanisms in neuroscience, cancer research, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine, offering a bridge between traditional 2D cultures and whole-animal models.

Related articles on model organisms

AI-Powered Hi-Plex Spatial Analysis Tools for Breast Cancer Research

Focus on Long-Term Imaging in 3D with Light Sheet Microscopy

A Guide to Model Organisms in Research

Development and Derisking of CRISPR Therapies for Rare Diseases

Multiplexed Imaging Reveals Tumor Immune Landscape in Colon Cancer

Imaging Organoid Models to Investigate Brain Health

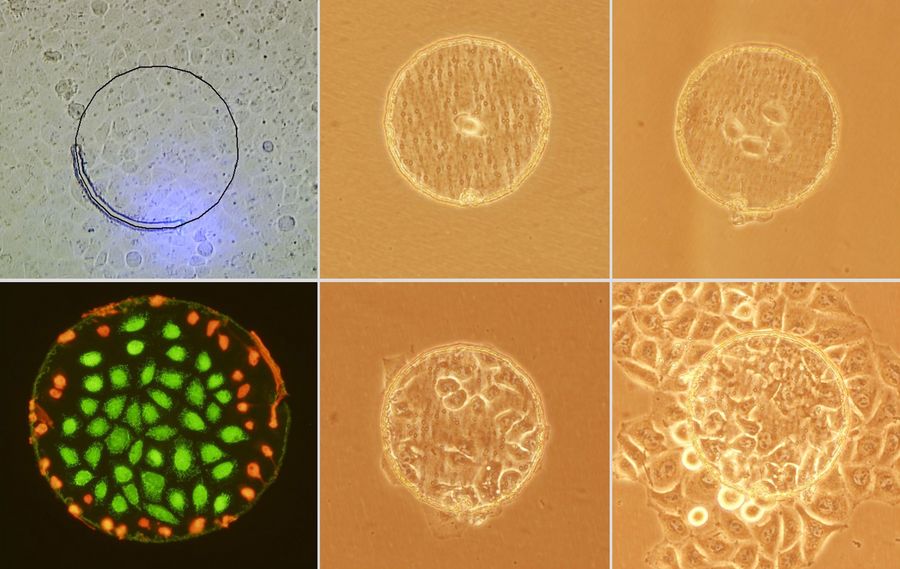

Studying cancer dynamics in real time

Live-cell imaging plays a vital role in cancer research allowing cell behavior to be observed in real time. Using techniques like fluorescence and time-lapse microscopy, researchers can track cell division, migration, invasion, and response to therapies at the cellular level. This ability helps uncover key mechanisms behind tumor progression, metastasis, and drug resistance. Live imaging also enables the study of dynamic interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironment, including immune cells and extracellular matrix. By using advanced models like 3D spheroids or organoids, rather than traditional 2D cultures, live-cell imaging provides more physiologically relevant insights. Overall, it supports the development of targeted therapies by revealing how cancer cells behave under various conditions and treatments.

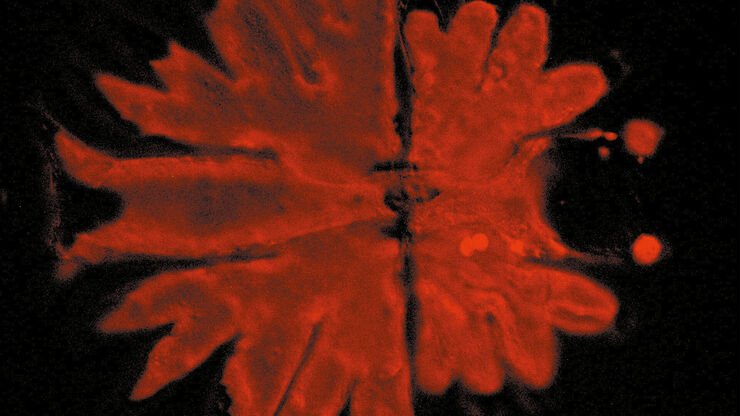

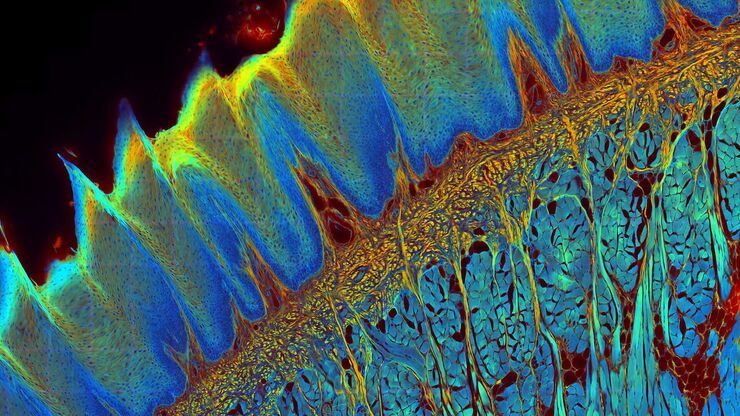

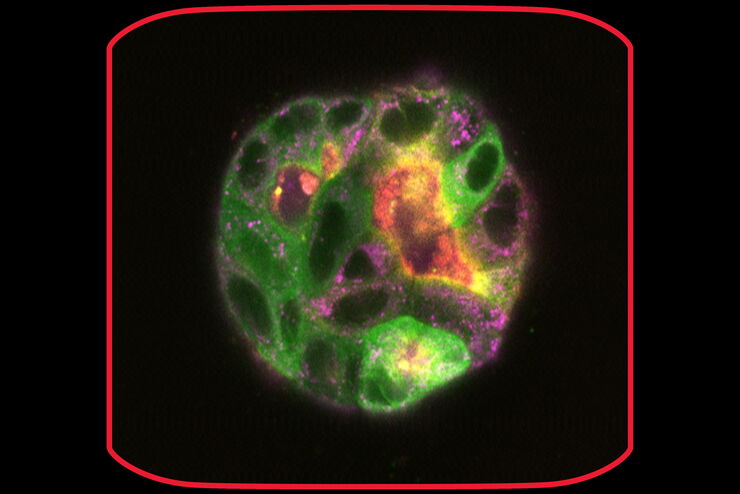

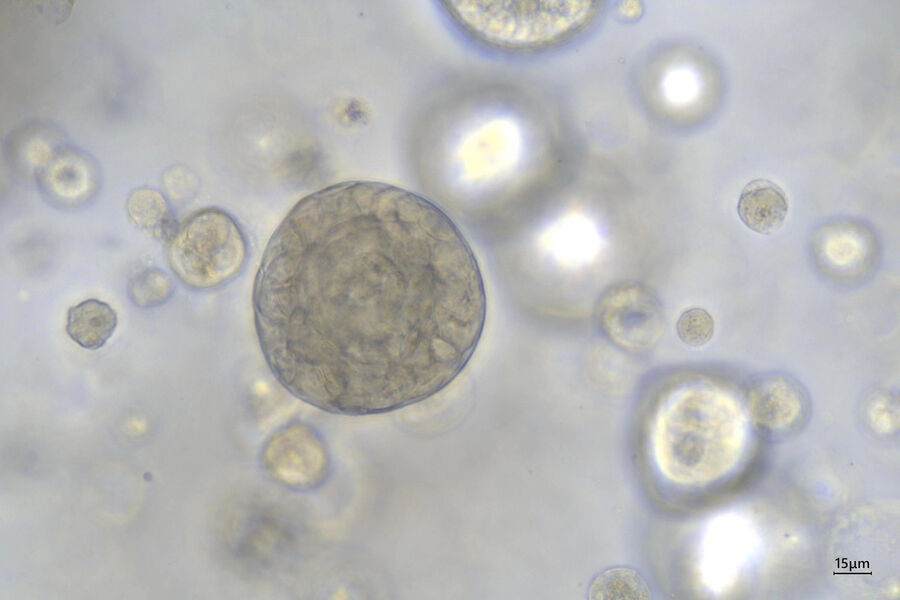

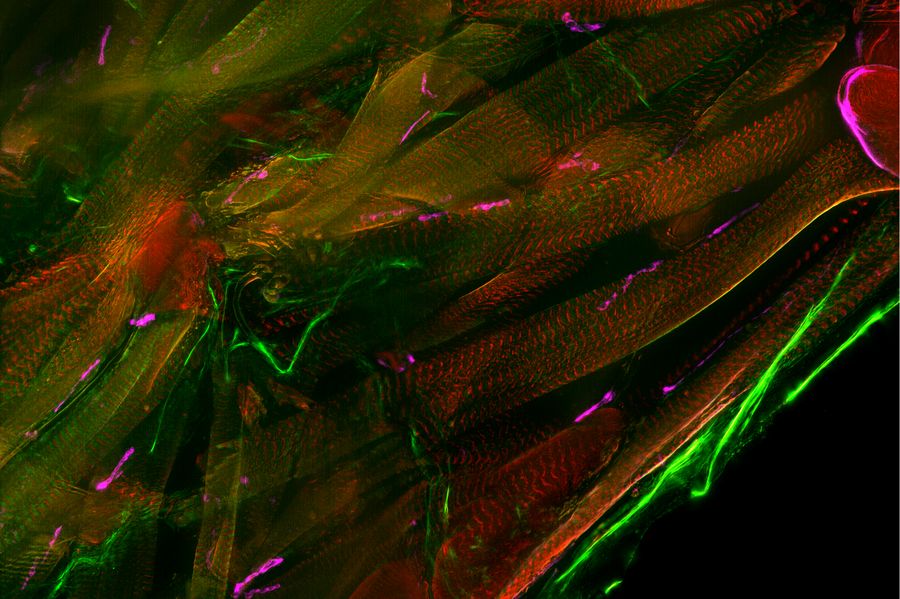

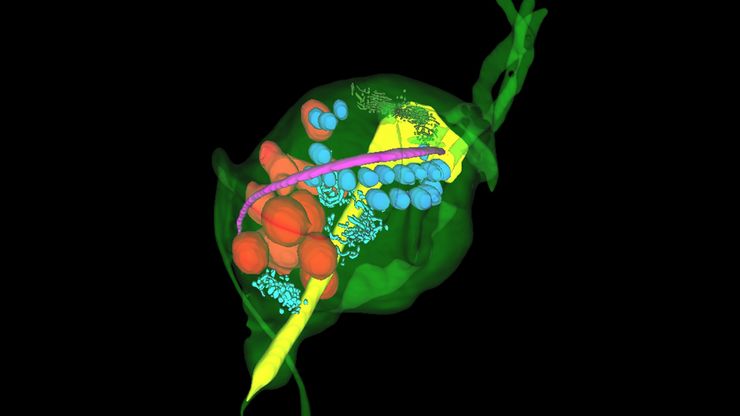

A 3D image of a spheroid self-assembled from HEK293 cells acquired with light-sheet microscopy. The spheroid was treated with the anti-cancer drug AZD2014, a recognized inhibitor of the mammalian Target Of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway which promotes tumor growth. Depth within the organoid is shown with different colors (see the z scale).

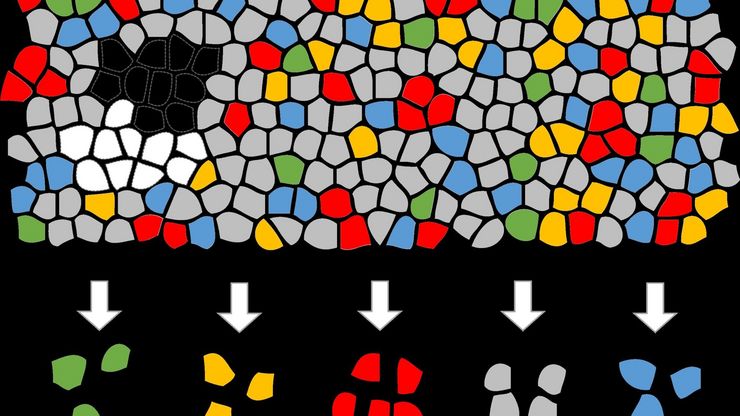

Live-cell-image optimization and analysis

Optimizing acquired images and analysis is crucial for live-cell imaging, enhancing the data quality and biological insights that can be gained.

- Deconvolution: It uses a mathematical algorithm to reassign out-of-focus information to its point of origin. Sharper images and better 3D impressions can be achieved.

- Computational Clearing: A real-time method that surpasses deconvolution by removing out-of-focus blur based on feature size and optical parameters. It enables clear visualization of thick specimens.

- Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM): SIM uses a grid to generate patterned excitation which can increase image contrast and resolution. For live-cell imaging, phototoxicity can be a problem.

- AI (Artificial Intelligence) Image Analysis leverages machine learning capabilities to generate reproducible segmentation results and fast 2D to 5D visualization.

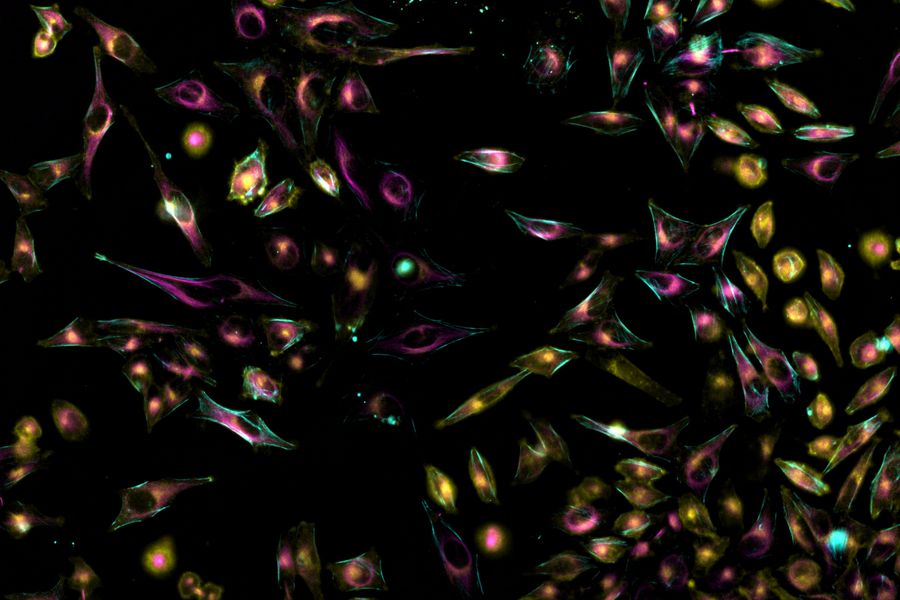

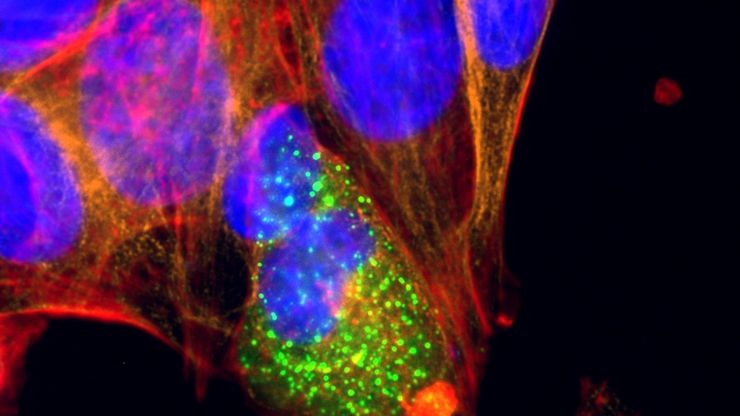

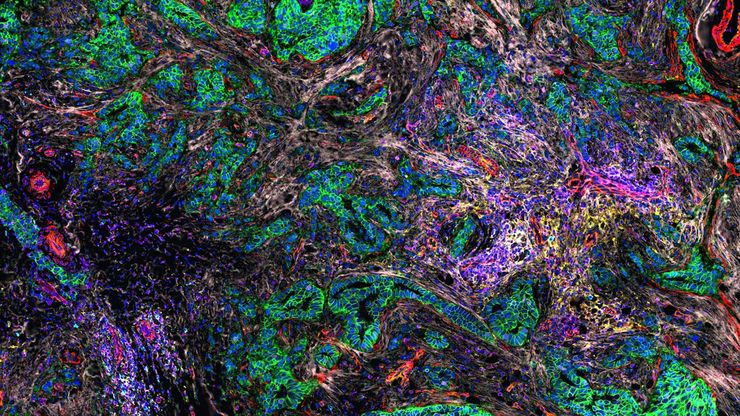

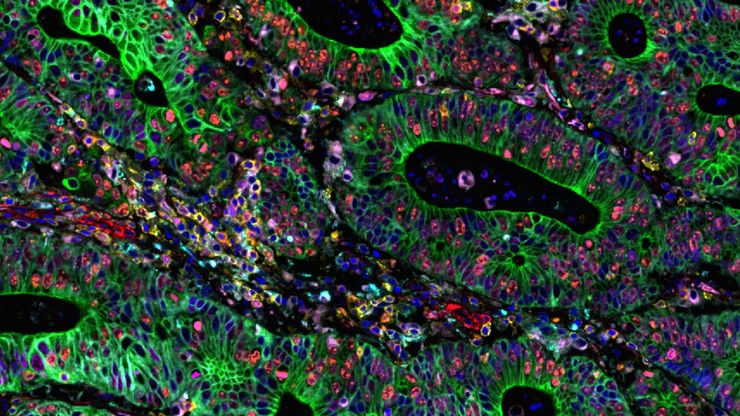

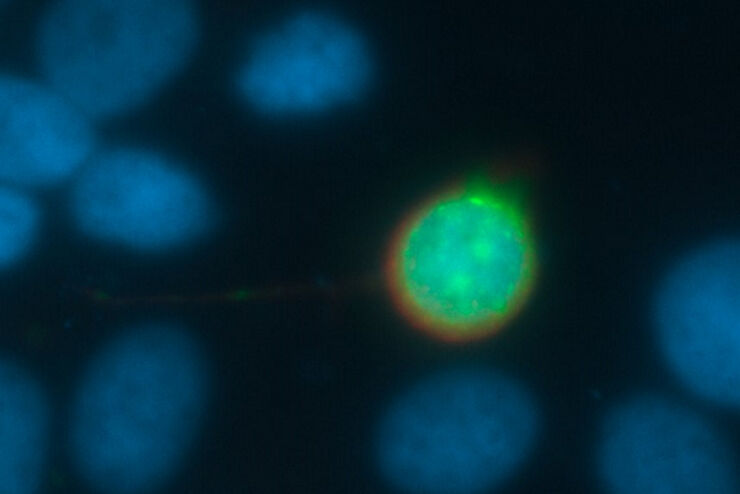

MIN6 cells grown as pseudoislets (pancreatic beta cells). Labelled with DAPI (blue), Alexa488 (insulin, green), Alexa594 (membrane receptors, red), and Alexa647 (phalloidin, white). Courtesy R. Bonnavion, MPI for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

Articles on image optimization and analysis

What are the Challenges in Neuroscience Microscopy?

Going Beyond Deconvolution

How to Remove Out-Of-Focus Blur and Improve Segmentation Accuracy

Volume EM and AI Image Analysis

How a Breakthrough in Spatial Proteomics Saved Lives

Microscope Calibration for Measurements: Why and How You Should Do It

FAQs

Live-cell imaging is a technique that allows researchers to observe living cells over time using microscopy, enabling the study of dynamic cellular processes like division, migration, and signaling in real time.

Common ones include widefield fluorescence microscopes, confocal microscopes, spinning disk microscopes, and light sheet microscopes. A microscope is chosen based on resolution, imaging speed, and phototoxicity needs.

Cells are maintained using environmental control chambers that regulate temperature, CO₂ levels, humidity, and sometimes O₂, replicating physiological conditions.

Key challenges include phototoxicity, photobleaching, maintaining cell viability, and minimizing focus drift during long time-lapse imaging.

Phototoxicity refers to cell damage caused by prolonged exposure to light. It can be minimized by using low-intensity light, shorter exposure times, more sensitive detectors, and gentler imaging modalities like spinning disk or light sheet microscopy.

Yes, with automated imaging systems, multi-well plates, and high-content screening platforms, live-cell imaging can be scaled up for large experiments.